Posts Tagged music theory

Numerical Notation for Saxophones Revisited

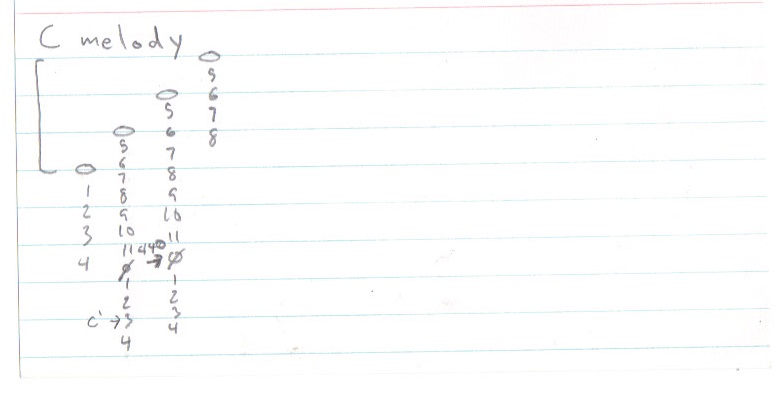

Been thinking about getting back into the sax. I could never be a great player, especially after taking so many years off, but it’s fun to play the horn, any horn, even if you are just making noise. I’d was thinking about getting a C Melody because I’ve just been working with guitar, bass and piano for several years and now I’ve got an ear for the real note values (not the Bb or Eb values) that I don’t want to mess up. I turns out the C melody sounds an octave lower than concert pitch. What I really want then is a C soprano, the only sax that plays the exact concert notes.

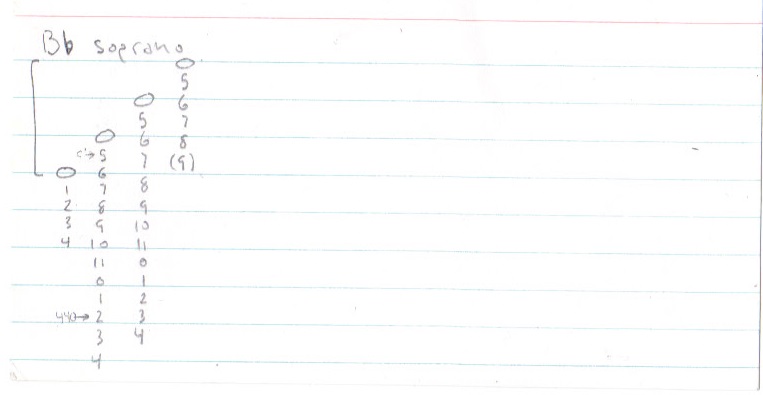

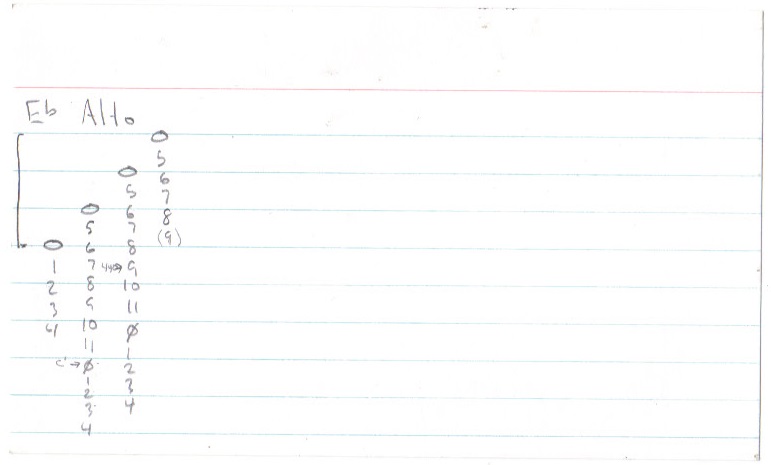

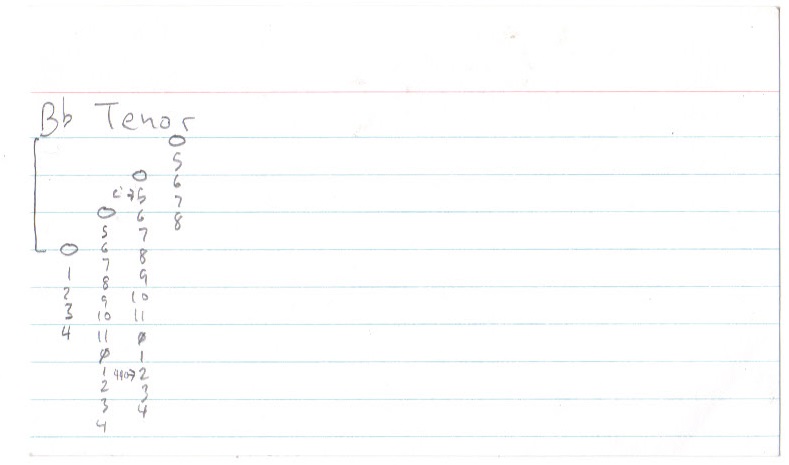

Except I don’t want to do that. Look, it doesn’t matter what I want. I’m kinda tired right now. But I haven’t posted in month and I need to keep going here. It was a nice break. But no one else really cares about this project at the moment, so it’s all me. And this has been bugging me. So I made some index cards like before, but less half-assed. (Have I mentioned repeatedly a major strength of numerical notation is the ease with which you can write it on ordinary index cards? It’s just something I noticed is handy.)

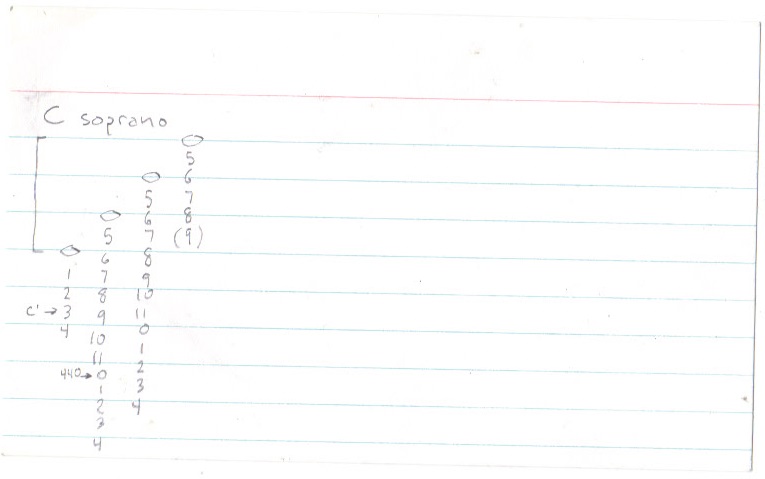

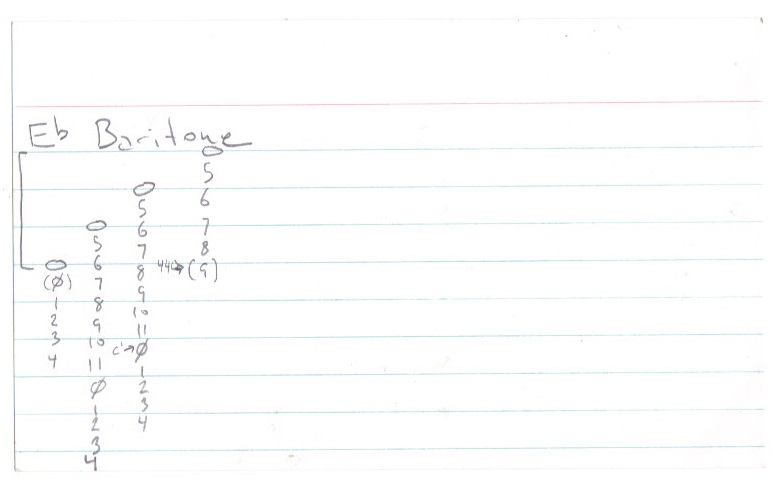

So I just went through the main saxes (including the C ones nobody really uses) and located middle C & A440. It’s as much for myself as anyone who is interested. (Which is maybe nobody. But maybe you. It’s only you… Did you know A440 is the highest regular note on a bari sax, if it has the extra key? I didn’t.) Here you go, and I hope it is helpful:

%

Staff System for Numerical Notation

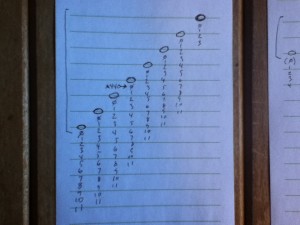

I made some quick sketches for my idea for a new type of staff system to get it out there. Each octave gets a line and the numerical value is written directly below. The standard graphical system for time value of the notes (whole/half/quarter/etc.) can still apply. Y’know, if yr into that sort of thing. (Shown is whole notes.) This is not written as something you’d play—altho technically you could mash down 12 keys at a time—it’s just an idea what it would look like:

Note that this is for a grand piano with 88 keys starting on low A. Most keyboards start on C and have less octaves. If you’re writing everything like it’s going to be performed by an orchestra, conventional methods are just fine and you certainly don’t need help from a moron like me. However, I find that the goal of writing music like that is little much for a student and not what they want to do anyway. So the task of writing music seems impossible and they never even really try it. This system is instrument specific; whatever keyboard you’ve got gets it’s own kind of staff. So it’s not some abstract system of every possible note you are dealing with, which you then apply to the instrument and see it if can hit it, but a very clear layout of all the notes available to you on the instrument in front of you.

Let’s take a closer look at how this works on another instrument: the saxophone. Various saxophones come in different ranges and keys, but the fingerings for the named notes are always the same. (Except some have a low A key or a high F#.) But the octave doesn’t start on the A for the the sax, it starts on D. It’s purely a mechanical feature of the instrument:

(A440 is going to be in a different spot for alto/tenor/etc.—it’s where things get complicated. Don’t worry about it.)

Now, if you know anything about the saxophone, you can see I’ve made a terrible mistake and left out an entire octave. This is not really a problem right now, because like the earlier posts, if I just put this thing out all at once looking great and making sense, some asshole is just going to put it on a t-shirt and no one will care where it came from. And of course, hardly anyone would use this system for piano or saxophone, it’s mostly useful for string instruments that can alter their tuning and range. (And maybe even for singers.) If you can figure out how to do this already, good for you. But I’ll keep working on better ways to present the idea. %

Numerical Notation and the 4ths vs. 5ths Paradox

There’s a smart sounding title, wonder if I’ve got anything to back it up.

Here’s the clock again from last post. The idea of naming the notes with numbers within an octave is dead simple. Scientifically speaking, two notes with a 2:1 ratio might as well be the same note.

YET,

It is not so. 0+5=the perfect 4th; 5+0(the octave above)=a perfect 5th. A simple counter-intuitive fact I have never heard explained or even alluded to in any music class or lesson. There are the Circle(s) of Fifths/Fourths presented to be memorized, but never explained. (This post is no exception.) But the simpler image of the clock with numbers can help. The 5th is thought of as the center of the diatonic scale, but chromatically it is the tritone. From any numbered note, we can see its tritone directly opposite on the clockface. And the fourths and fifths are not merely about counting semitones but knowing which direction they are coming from and going. 5 places clockwise is the 4th and 7 is the 5th and vice versa. Then when you get into extended chords and intervals you can see the value of the 24hr clock. Memorizing these values is much simpler than letters with arbitrary accidentals. So there. %

Continuing Numerical Notion

I get that this whole idea makes it seems like turning music into math and that is going to seem uncool to some people. I am not trying to make math seem cool. Advanced math is interesting to me because it’s completely beyond my comprehension. I know that it makes sense, but I don’t know how. I’ve never been a math nerd. Trying to explain music theory to someone who understands Calculus and Physics like it’s something that don’t immediately understand fully already makes me seem like the moron I am.

This is not advanced math, it’s very simple. Think about why Math sucks, C- minus Algebra I students who taught themselves guitar or whatever. It’s the bullshit like memorizing multiplication tables and equations, right? It’s the exact opposite of fun. Advanced Music Theory is kinda the same thing. You’ve probably noticed this if you tried to pick up a book on it but didn’t want to admit it. It’s not the subject matter, it’s the thought process. The Circle of Fifths is just like multiplications tables. They just tell you it makes sense without explaining it and you have to drill it and memorize it. Most people just muddle through. If you do learn it, you just know it without really understanding why it works. That’s my experience. Musicians (even some teachers) either don’t learn theory or don’t really understand it.

I think there’s a way to break it down. Just like you can break multiplication down into addition. It takes a little longer at first, because if you just memorize the answers you can just spit them out. But with practice, it’s gonna be just as fast and eventually you’ll know it the same, but you’ll also know the reason for the answer.

When you use numbers for the notes, the interval is apparent through simple subtraction. Here’s a chart for the differences:

1=minor 2nd (half step)

2=major 2nd (whole step)

3=minor 3rd (step & a half)

4=major 3rd

5=perfect 4th

6=tritone (aug. 4th/dim. 5th)

7=perfect 5th

8=minor 6th

9=major 6th

10=minor 7th

11=major 7th

And of course a difference of 12 is back to the same number an octave higher or lower. I’m working on a modified staff system to make this practically useful as written music for an instrument. But you’ve got to understand how this works as a concept first.

At this point you might be thinking this is not very useful for music that spans more than one octave, which is most music you’d want to listen to. Or hell, even any scale that doesn’t start at 0 has to cross over 0 and why are we doing this again? You’ve got to keep in mind that with lettered notation you’re doing the same thing with arbitrary values. The note after G is G# and the note after that is A. Then A#, then B, then C. Quickly then, what is the interval between A and C? You can either memorize that this is minor 3rd, or you can subtract 0 from 3. Easy. But what about G to C? It’s better to think of it like a clock:

It helps to be on military time. You’re going to have to trust me on this. %

Understanding Why Lettered Notation is Illogical

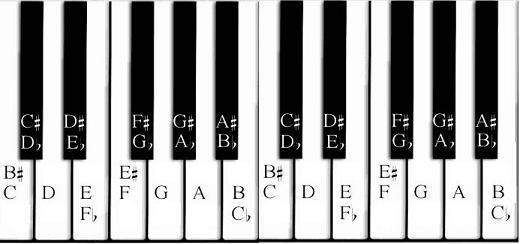

Music is not Science. There’s some interesting sciencey things about music, but music itself doesn’t have to perfect or logical. Classical notation using letters is a great example. It hasn’t changed for hundreds of years altho the values and assignments are largely arbitrary. Here’s the notes on a keyboard:

Most pianos and keyboards will be tuned to A440 in equal temperament. Some have an issue with this but my beef is the assignment of the black and white keys, or really the concept of flats and sharps as they are assigned to the letters A-G.

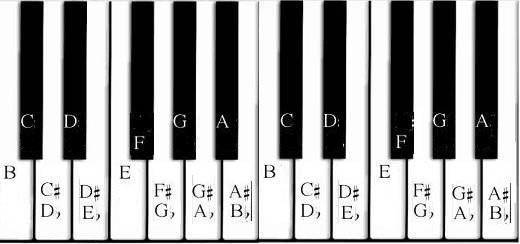

The argument against redesigning this system from scratch may be that music is more about intuition than logic and that the existing system has prevailed precisely because of this and anyway, it’s all pretty logical it you study it long enough. But this is the problem. It only seems right because you accept these arbitrary assignments as a kind of Truth that is unquestioned. Staring from this, a logical construct is formed around it that supports itself and eventually, seems intuitive. But really, the process involves rote memorization which is wholly unintuitive. For example, the notes A and B are a whole step apart, but B and C are a half step. Why? There is a historical reason, but also, the notes themselves must be considered as nonsense. The white keys on the piano may seem “brighter” sounding or more “natural” in some way but this is only through repetition, ear training, and relative placement of notes. An older standard of note values places the A above middle C at around 415 Hz, a full half-step below A440. If a keyboard is tuned to the values of the notes when those notes were invented, the keyboard looks like this:

Unless you have perfect pitch (trained to 440), you might not even notice a piano has been tuned this way. It might sound off at first, but you’d get used to it. Time has proven this. The system of equal temperament is another example, but regarding the intervals. We are accustomed to hearing notes and intervals slightly wrong from what they were first intended to the point were the “right” values now sound wrong. Eliminating the arbitrary system of letter values with sharps and flats would make learning notes and intervals easier for new students.

%

Recent Comments