Posts Tagged music theory

How many notes are there?

Here’s another video by someone else. Maybe I should make videos at some point. Sorry if I keep going over the same material but no one really seems to be paying attention, I’m just ironing out the concept more and more. Hopefully.

How many keys are there?

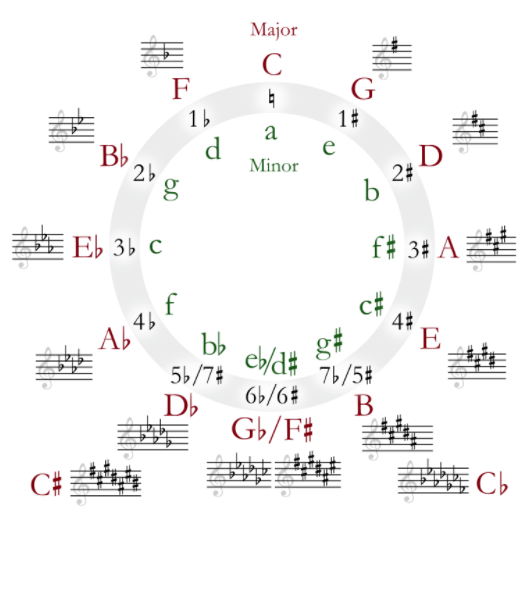

Here’s a clip of Victor Wooten explaining a very basic concept of music theory that is not always explained so simply. The answer you get is easy once you know, but it’s not the intuitive answer. Even he got it wrong at first. Why? Because in traditional music theory there are 6 keys that overlap:

(this image from the circle of fifths wiki does not even bother to name a♯ and a♭ which is…interesting)

These keys, disregarding the sharp/flat system, contain the same notes. Sure, if you are intentionally doing something clever with modulation in a piece, like going around the Circle, you would never go from E to C♭ in your head or on paper, but the sound is no different in equal temperament. (Just noticed I’ve been spelling “temperament” wrong for as long as I’ve been using it. Never heard the “a” pronounced, that’s something new.)

This matters (to me) because as I’ve said in the previous posts, there’s nothing inherently “natural” to the “natural note”. There’s only the note you start on and the intervals. Take the point that modes are not keys but scales. If you are playing in C, you can start playing a C scale melody but let’s say you switch to playing the Dorian mode. The key hasn’t changed, you are still playing entirely on the white keys, but the tonal center has, and the intervals of the scale have. That’s a difference you can hear. There’s a game you can play with traditional music theory that I’ve come to appreciate more than dismiss the more I get into it, but the average person (non-musicians; people without perfect pitch) really are never going to. That’s fine but it’s not the thing I’m interested in. Hopefully I can spend more time on interesting things in the future.

Gamelan & Sonic Youth

In many ancient traditions and contemporary settings, music is not written out for the performance. It’s worked out among the musicians, maybe by a lead composer type all at once, or by the group over a period of time. The piece or song is memorized and maybe at some point has a life outside that group of musicians, so it becomes like an oral tradition of storytelling.

So, let’s say you wanna write that down. Seems reasonable that you’d try to do this with the tools you have, which is staff notation invented for western orchestral music. But unless the musicians in question were also trained in this method and set out to follow the rules as such, you are going to end up with a crude approximation. Two examples I’ve been really interested in over the years is traditional Balinese Gamelan and the 80s-90s work of punk/art rock group Sonic Youth.

Worth noting that Gamelan music has a native written form (a few in fact), and that the harmonic ideas of SY have roots in the music of avant garde composer Glenn Branca, who has his own presumably meticulous system. But in practice, both of these types are just winging it. In addition to not adhering to a preexisting written standard, they also both are using either bespoke or customized instruments and tunings. (Really hate the use of “bespoke” to mean “custom” but it fits here.) A Gamelan orchestra—all the gongs and metallophones—are made as a piece, tuned to itself. Each player isn’t bringing the reyong or gangsa they are leasing from Guitar Center, these things only exist together as one thing and can’t be individually adjusted. If one were lost or broken, you can’t even swap one out from another group. Likewise, when SY’s van was stolen in 1999, the sound of the band was heavily impacted. They were touring with 24 heavily customized guitars; almost a different set for each song. All of the older songs from that point had to be reworked and relearned.

Here’s the most comprehensive list of SY tunings, which, despite appearing to be a fan site in design and guesswork is in fact their official site. The band themselves apparently did not keep exact notes and any 3rd party’s detective could be just as good. I have even seen versions that note differences in the unison tunings (i.e. “second D slightly flatter”) and this is where a decimal system of tuning would really be helpful.

It’s these slight differences that create a sound totally different than what can be achieved through normal western intonation. The shimmering textures most…notable…here are created very deliberately (tho not always exactly or uniformly) by the dissonances that are reduced or edited out completely of regular music.

The very complex numbers that you can wind up with when referring to a note by it’s frequency in Hz can be replaced with a simple “𝑥.𝑥𝑥” by using the 0-11 formula and then the deviation .01-.99 in cents, ultimately leading one to a very snappy conclusion.

Fixed Interval Notation: Why…are you? Doing this! To me!?

Look, you came here, alright. This whole thing could be meaningless. I mean everything. But let’s not worry about that. What is just this thing about? Let’s think about Jimi Hendrix again. Most people will say he tuned his guitar to E♭, sometimes D; that is, tuning to the entire guitar down a half or whole step. (It’s complicated by analog recording and playback, the standard of those days. If the speed of either changes, the pitch changes.) If you aren’t using a tuner, this sometimes becomes the default accidentally by tuning to the top string (standard E) which naturally becomes flatter over time. If the notes really matter in themselves, this would change the name of every scale and chord that you play. It doesn’t. That’s because you aren’t tuning to E♭, you are tuning to A=415 or thereabout.

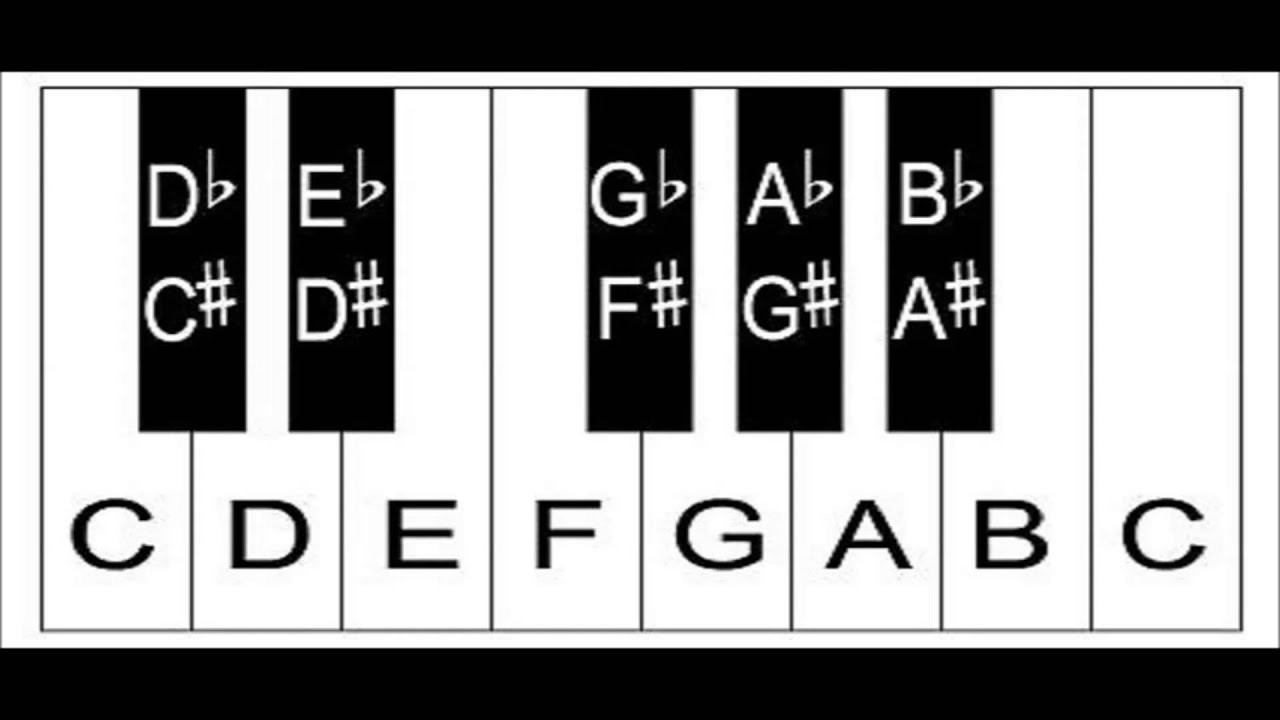

And this is The Problem that led me to this Whole Thing. Learning music as a kid on a horn or strings, you learn that the instrument tends to go flat, and when the orchestra plays in a group it tends to be flatter than the piano. This is known as classical pitch and it’s about A=430. It’s a good idea to have the standard be a little sharp, right? So you tune to the piano and it lands in the ballpark. (If you are playing along with a piano, you’d want it to stay there as close as possible. Most beginner orchestras don’t play along with a piano.) But I’ve gone back and researched it, and you can read the wikis I hope, it’s not just a small adjustment to the standard historically. It really was 415 and one point, which is fully A♭ today. At another point in Germany it became 466, which is A♯ (or B♭). Take a look at the keyboard:

If you shift the tuning a half-step in either direction you get chaos with the the names of the notes. But there’s nothing special about the frequencies themselves that make the white keys the Natural Notes, and the black keys Accidentals (in the Key of C Major, A Minor or any of the traditional church modes). Think about the Modes. They are the first scales in Western music, right? That’s why it’s those keys. But to really hear how they sounded, you have to shift them down a half step. Seems…crazy. But isn’t that WHAT THEY WANT YOU TO THINK? No. It’s not. If “they” is music teachers, they definitely don’t want you to think about this because it’s really distracting and YOU’VE GOT TO FOCUS.

Fixed Interval Notation: Limits of Use

Hm, sounds legal. Not really, but it’s occurring to me now I’m making a system that’s more for analyzing than composing. Having some latitude with changing what frequency the note “A” is, for example, is pretty useful is some cases. Jimi Hendrix, for example, tended to tune down his guitar a little, probably just by ear. In FIN the note might be called 11, or 11.5, or 11.75. The more complex a number it is, the harder it is to read off the page. But if you just want to know what the exact note someone else is playing, it is useful information. I’ve tried making a simple equation to translate the frequencies (in Hz.) to simple decimal numbers, but you run into a problem pretty quick. Let’s ease into this with this very simple, randomly selected video:

Now it gets a little more complicated:

So you see there’s some more work to do. Think about it.

Recent Comments