Here’s a clip of Victor Wooten explaining a very basic concept of music theory that is not always explained so simply. The answer you get is easy once you know, but it’s not the intuitive answer. Even he got it wrong at first. Why? Because in traditional music theory there are 6 keys that overlap:

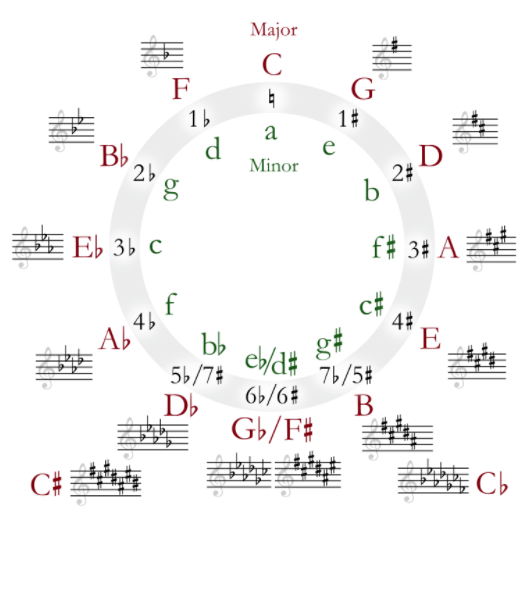

(this image from the circle of fifths wiki does not even bother to name a♯ and a♭ which is…interesting)

These keys, disregarding the sharp/flat system, contain the same notes. Sure, if you are intentionally doing something clever with modulation in a piece, like going around the Circle, you would never go from E to C♭ in your head or on paper, but the sound is no different in equal temperament. (Just noticed I’ve been spelling “temperament” wrong for as long as I’ve been using it. Never heard the “a” pronounced, that’s something new.)

This matters (to me) because as I’ve said in the previous posts, there’s nothing inherently “natural” to the “natural note”. There’s only the note you start on and the intervals. Take the point that modes are not keys but scales. If you are playing in C, you can start playing a C scale melody but let’s say you switch to playing the Dorian mode. The key hasn’t changed, you are still playing entirely on the white keys, but the tonal center has, and the intervals of the scale have. That’s a difference you can hear. There’s a game you can play with traditional music theory that I’ve come to appreciate more than dismiss the more I get into it, but the average person (non-musicians; people without perfect pitch) really are never going to. That’s fine but it’s not the thing I’m interested in. Hopefully I can spend more time on interesting things in the future.

Recent Comments